Power, Protection—and Purpose

Text: Luke 3:17: "His winnowing-fork is in his hand, to clear his threshing floor and to gather the wheat into his granary; but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire."

What I have to offer in this sermon is less a central message and more a short series of observations that I’d like to invite you to think about.

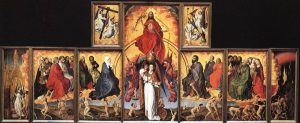

Andrea Mantegna (c.1431–1506), "The Baptism of Christ," Church of Sant Andrea, Mantua, Italy (Wikimedia Commons).

The first is simply a reminder of where we are in the calendar. We have arrived the first Sunday after the feast of the Epiphany, and that means we recall today the baptism of Jesus by John in Jordan. Things are slightly out of sequence, because for the next couple of weeks we’re going to go back over the earlier years in the life of Jesus; but for now we’re at the moment when epiphany meets theophany, a fancy way of saying that the public acknowledgement of Jesus as the fulfillment of God’s plan, a thing first done by John the Baptist, is joined together with this sign of God’s presence in the descending dove and the voice that is heard from heaven.

So this annual cycle in the calendar is meant to invite us to reflect for a moment on just what Jesus’ baptism means for us, and more specifically what it means for our own baptism.

Keep that in mind, and then consider that there are three very distinct and not necessarily harmonious themes in the readings we’ve heard this morning.

One theme, the one that dominates the psalm we sang together, is the power of God. And it’s not just anything about God that is powerful; it’s specifically the voice of God that has the psalm fascinated. The voice of God is so powerful that it break trees, it splits flames, it shakes the wilderness, it strips the forests bare. The voice of God is something like a tornado.

And that makes sense, at least in one way, because it is the voice of God that is so powerful as to bring in the whole creation. Remember how the first creation story works in Genesis; God says things, and they happen. God speaks the creation into being. And it is the same voice of God that announces the face of who Jesus is, at least to anyone who has ears to hear.

We might ask today: Why don’t we hear that voice, that voice of such power that it can even be destructive, why don’t we hear that voice speaking any more clearly today? Why don’t we hear it above the truly awful, angry shouting that so fills our public square? Why doesn’t the voice of the Lord speak up to drown out the hate, and the intolerance, and the bigotry, and the self-justifying morality?

A second theme, along with God’s power, is God’s protection. The words from Isaiah this morning are words written to an Israel already in exile, to a group of people who have already lost their home to war and chaos and are trying to make a home in a place where they are unwelcome. Maybe, if you listen to the news these days, that sounds familiar.

Listen again to the words that come from the voice of the Lord to them:

Do not fear, for I have redeemed you;

I have called you by name, you are mine.

When you pass through the waters, I will be with you;

and through the rivers, they shall not overwhelm you;

when you walk through fire you shall not be burned,

and the flame shall not consume you.

For I am the Lord your God,

the Holy One of Israel, your Savior.

You might hear those words as the poetic language of prophecy written thousands of years ago to comfort the people of Israel and help them hang on to a common identity when they had been scattered throughout the ancient world.

Or you might hear those words sitting in church this morning as words revealing something about God’s acting to save all people through the incarnation in Jesus, through the life, the teaching, the passion, the death, and the resurrection of Christ.

Or you might instead consider how those words would sound today to a family sitting in a refugee camp in Turkey, or in an immigration detention center along the border, or in the cities in Syria being systematically starved to death by factions striving for the upper hand in a bloody civil war.

The assurance of God’s comfort, of God’s protection, may seem disconnected or even somehow irrelevant to us. By any measure, we are comfortable; by any measure, we are safe. But to millions of people living under the shadow of violence, desperate for the most basic accommodations of peace and stability, these words hold what little hope there is left in the world.

If you look at Hymn 636 in the hymnal, you’ll see how Isaiah’s words assuring God’s protection were turned into one of the great hymns of the eighteenth century:

“Fear not, I am with thee; O be not dismayed!

For I am thy God, and will still give thee aid;

I’ll strengthen thee, help thee, and cause thee to stand,

upheld by my righteous, omnipotent hand.“When through the deep waters I call thee to go,

the rivers of woe shall not thee overflow;

for I will be with thee, thy troubles to bless,

and sanctify to thee thy deepest distress.“When through fiery trials thy pathway shall lie,

my grace, all sufficient, shall be thy supply;

the flame shall not hurt thee; I only design

thy dross to consume, and thy gold to refine.”

The idea behind these words expands beyond God’s protection to encompass one last thing for us to think about this morning. It is the idea that within the difficulties, within the turmoil, within the challenges we face there is a purpose, even a holy intention, that may or may not be something we can make sense of.

There’s tension between this and what we’ve been hearing so far. Yes, God is the God of power, indeed God is the source of all authority, whether we acknowledge it or not. Yes, God will act, and has acted, to protect us in our vulnerability and in our weakness.

But that is not all. The story of the baptism of Jesus is not only a story about how our own baptism brings us under God’s protection. It is a story about how we are made part of God’s purposes. And those purposes are, in some basic way, divisive.

When John speaks about Jesus to the people around him, the image he gives them is not just an image of power and protection. It is a clear message that in being baptized, in setting off on his life in ministry, Jesus has a purpose—and that purpose is one of clarifying things by setting them apart, one from another.

That’s a hard message for us to hear, and it’s a hard message to preach. We want to hear the words of comfort, and they are true. We want to hear that God accepts us and affirms us, and that is true, too—but it is not the whole truth.

When Jesus steps forward to be baptized, he is making a choice. That purpose is not just to give us the means of reconciliation with God; it is to set a choice before each one of us, too.

In a way, that choice is whether or not to follow the example Jesus has set. It is whether or not to be baptized—to be united with him, as Paul says, in a baptism like his.

But that involves a great deal more than simply living through a sacramental act of the church. It means working to align the choices we make, little choices and big choices, with the purposes of God.

Plenty of folks who are baptized never actually confront that choice in a conscious way. It may be because they were baptized when someone else made the choice for them. Or it may be simply because they haven’t yet figured out, or don’t quite yet grasp, that there really is a choice to be made, there really is something at stake, in choosing to align yourself with God’s purposes—to be part of that purpose.

Jesus, who is the God of power and the God of protection, Jesus is also the God of holy purposes. In his baptism, Jesus chooses to take on that purpose as both his identity and his work. And the choice Jesus makes sets before us, each one of us, a choice as well.

The faith we are given is a gift. But like all gifts, not everyone who receives it makes anything of it. Not everyone who receives it does anything with it. Not everyone who receives it cares for it, tends it, works to help it flourish.

This work of ours, this being aligned with the purposes of God, it is not something that comes naturally. If it were, we wouldn’t need the church. And there are plenty of people, maybe even some of us, who don’t really think we need the church.

But the truth is, we can’t be part of God’s purpose without it—because we can’t summon the discipline, the support, the help, the encouragement, to keep making that purposeful, life-giving choice. That is what is held before us today as Jesus walks into the waters of the Jordan, and bids us to follow. Amen.