Reversal of Fortune

[No audio is available for this sermon.]

Text: Jeremiah 31:13: “I will turn their mourning into joy, I will comfort them, and give them gladness for sorrow.”

Things come a little out of order for us this year. Epiphany, that happy moment of Jesus being manifested as the promised one to people beyond the event of his birth—and in particular to the three visiting dignitaries from the East-—doesn’t happen for two more days. We are still this morning firmly in Christmas, indeed on the eleventh day of Christmas; you should be on the lookout for lords a-leaping today.

Now, a great many churches will cheat on this this morning, and bring Epiphany forward a couple of days. After all, it’s a feast day; we only ever get to have Epiphany on a Sunday if Christmas falls on a Tuesday, and that won’t happen again until 2018. So you pretty much have to cheat if you’re going to get the Three Wise Men all the way to the manger and get to sing all five verses and five refrains of “We Three Kings of Orient Are.”

Here we are more disciplined than that. Or perhaps, more honestly, I want to squeeze every drop out of the all-too-short season of Christmas that I can this year.

But here’s the funny thing: If you keep Christmas all the way to the end, the readings you get from the gospel lessons actually come after the events that are always the story of the Epiphany. You have to wait another two days for these guys to get to the manger; but already this morning Joseph and Mary have been warned to get up, get out, and get over to Egypt. Things have gone from bad to worse for them in a very, very short amount of time. They are quite literally running for their lives.

The other gospel lesson we might have heard this morning—we had to choose from among three—comes from much later in the life of Jesus, when he’s twelve years old and in the habit of disconnecting himself from his parents in large crowds. It’s the story of Jesus staying behind, teaching in the Temple to an audience of much older rabbis, while his parents frantically realize he’s missing from the caravan.

It turns out we have both of those stories in stained glass; but Mr. Skinner made the images in the glass appear in the right order, first the nativity, then the Epiphany, then the flight to Egypt, and then the boy Jesus teaching in the temple. The building gets right what the lectionary confuses.

Things may be a little out of order, but the point these stories communicate is the same, no matter how you approach them; Things that are seeming to go well suddenly go bad. A child whose birth is heralded by angels, who seems to have a path of triumph before him, is suddenly and dramatically facing very bad odds. The most powerful person in his world wants him dead. Or—what might seem less serious, but if you’re a parent isn’t at all—a boy in early adolescence is lost in an urban throng far from home.

This is the stuff of our lives. We all live just one hair’s-breadth, just one phone call, just one bad meeting, just one blown exam away from disaster. We have worked so hard, tended our little fires, guarded our hopes with such care; but we know—we just know—that it can all be swept away in a fleeting moment.

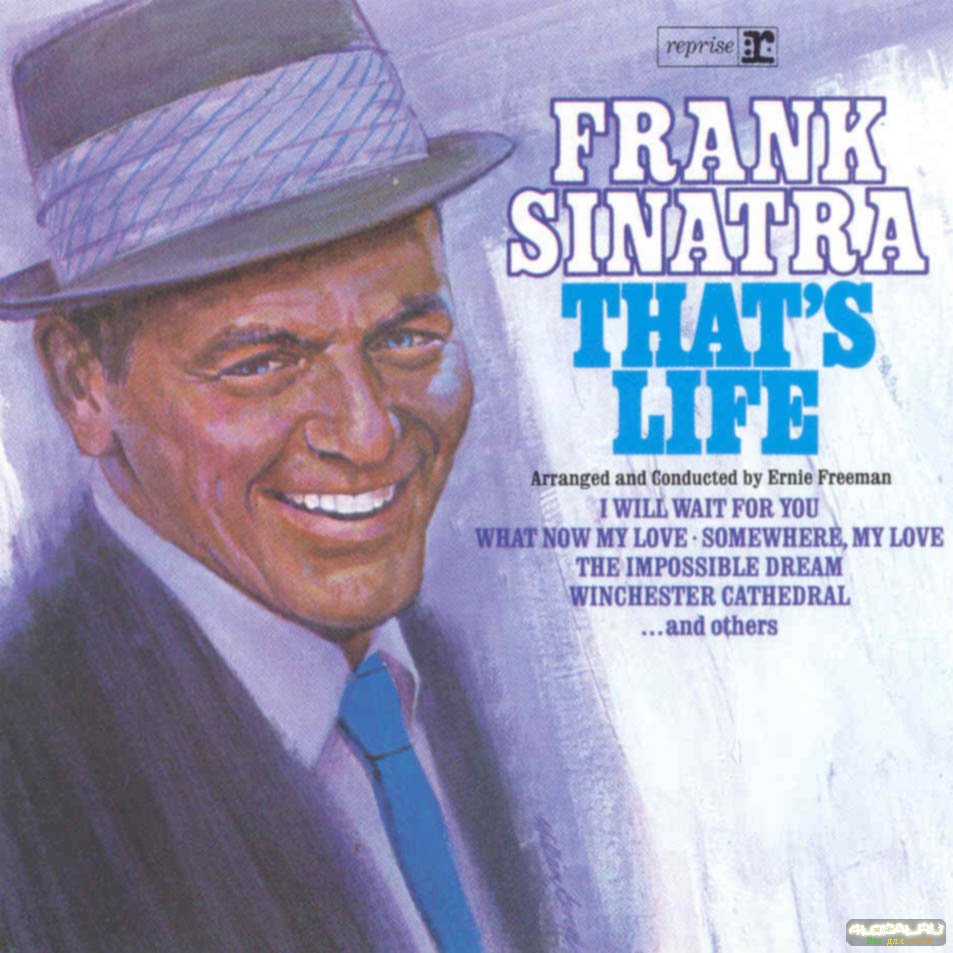

As that well-known theologian Frank Sinatra once taught, “That’s life—that’s what the people say; riding high in April, shot down in May....”

Most of us, I would even say all of us here in our community, know what it’s like to live lives on this balance beam between possibility and disaster. We know what it’s like to feel as though everything is going our way, that we’re large and in charge and we know what it’s like to feel as though we have pretty much lost our last bet.

And one of the very real advantages of having been a part of this community as long as I have is that I could pretty much cite chapter and verse of times that each one of you have been on one side or another of the roller coaster of good fortune. And I know you could probably do much the same with me.

That’s life. That’s what the people say. So why talk about this in church?

Our lives are so fragile. When we have succeeded, when things have gone our way, we think we are invincible. When we have stumbled and fallen, when we don’t feel as though we could even show our face again, we think we are beyond hope—even beyond redemption.

The reason for talking about this in church is that it turns out to be the same with the boy Jesus, the young Jesus, the man Jesus. Jesus knows this harshness of our lives, as deeply as we know it ourselves. Things go wrong, very wrong, for Jesus and for his family. Jesus goes from mountaintop to desert valley more than once in his short life. And at the end he knows the greatest reversal of all—being abandoned by his friends.

And yet—and yet—he does not lose faith. He loses fame, he loses reputation, he loses friends—but he does not lose faith. Why?

Why doesn’t he give up? Why doesn’t he get angry at God? Why doesn’t he decide the whole thing is a delusion—as so many of our contemporaries seem to have done?

I can’t help but think that part of the answer is that Jesus knows the promises God has made—something we don’t really think too much about ourselves anymore. I can’t help but think that it comes in part because Jesus knows his Old Testament, knows it better than we know our own Bible.

And he knows this promise that Jeremiah speaks this morning: I will turn their mourning into joy. I will turn their sorrow into laughter. I will make it right. I will not abandon you.

Jesus makes a choice about the relationship he will have with God. He could wait to be convinced; he could wait for proof.

Instead he chooses to be all in. He chooses to start from the position that God will live up to the promises God has made. Jesus doesn’t need to know how, doesn’t need to have proof, doesn’t need to have evidence. Doesn’t need any of that.

I can’t help but think this must come in part because of the experiences of Jesus’s earliest days—this terrible threat, a threat of murder, that comes to his parents; and his parents’ absolute trust in God in responding. It means leaving what little home they have, what little hopes they have, and striking out on their own to an alien place; but they do it, because they trust God’s promises.

There is no reversal of fortune we can experience, absolutely none, that Christ will not endure with us. That is the upshot of these stories. We can’t change the fact that life is fickle, that fate is cruel, and that our lives are not nearly as stable and secure as we would like them to be.

But in all of it, absolutely all of it, a loving God comes with us. And that God is the God who has made this promise: However dark the darkness is, however deep the hole is, it is not the end of the story. It is never the end of the story. There are promises—God’s promises—to be kept, to you. The only question is whether we will respond in kind. Amen.