The Other U.F.C.

Text: 1 Corinthians 1:10b (J.B. Phillips): “...speak with one voice, and [do] not allow yourselves to be split up into parties. All together you should be united in thought and judgment."

It should surprise none of you that the rector of an Episcopal church is an Anglophile, and even a mostly-out-of-the-closet Anglophile. You may have noticed the biscuit tin with Winston Churchill in the rector’s office, the gift of a parishioner who saw into my soul and saw...tea and scones.

Over the past year or so I have significantly increased the portion of my media diet that is given over to British news channels. I’m interested in the political process there, and in the conversation about leaving the European Union. I’m envious of the incredible efficiency with which changes in government happen—no endless campaigning cycles. I like the fact that most people in Britain simply accept without question the premise that everyone should have access to health care, and that the best way to make sure that happens is to create a system of national insurance. It’s not easy, it’s not cheap, people fight about it, yes, but the simple fact is that among all the nations in the world they’re ranked twentieth in life expectancy, and we’re ranked thirty-first.

I’m telling you all this because through my newly increased intake of British media I’ve also learned things about aspects of British life that I don’t really care much about. And number one on that list is professional soccer. It is a huge business in the U.K.; everybody seems to have their favorite team; it’s a matter of nearly tribal loyalty and fervor, and historically the lands of British Isles have shown some expertise in tribalism.

I have noticed that a few teams, and a few of the very best-known teams, have a particular kind of name. Like most professional sports teams virtually all of them are named for the city they call home: Liverpool, Manchester City, Chelsea, Leicester City, Everton, and so on. There are exceptions to this, like Arsenal and Crystal Palace; but you get the idea.

Now, even though they all play soccer, all of these teams are formally called “Football Clubs.” And if you look on their websites, you’ll always see somewhere the abbreviation F.C. Some of them are “A.F.C.s,” which I’ve learned means that they are athletic football clubs; I’m not sure what that says about all the others.

But some of them—some of the most important, best known, wealthiest ones of all—have a different distinction. They are “U.F.C.s”—United Football Clubs. Probably just about the best-known soccer team on the planet is the Manchester United Football Club.

Because of the way my head works I started to get interested in why some teams are called “United” and others aren’t. It turns out that each of those teams has a story about starting out in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century in a relatively larger city with a few teams scrambling for players and fans, and almost always a story about one or more of those teams going bankrupt, and then somehow putting the pieces together by joining forces and creating a single new entity—a united club—that would be stronger, healthier, and attract more supporters.

That model became so significant that in this country, when major league soccer got started, some brand new teams decided to call themselves “United”—D.C. United, Minnesota United, Atlanta United. They sort of missed the point about exactly what “united” meant, but I guess they liked the example of the older teams that had to name themselves that way.

So if you pay any attention to sports journalism in the U.K., you know that “U.F.C.” means one and only one thing: United Football Club. It’s a way of joining forces to do better at gathering supporters for a specific and passionate task.

That’s a long introduction to a short idea. We, too, are a U.F.C. But we’re a different kind of U.F.C. Or at least we’re supposed to be.

The Christian faith is made up of a few deceivingly simple ideas:

- We are all fundamentally and radically equal before God, no matter what our status in this life, because we all live under the condition of human moral frailty. God acts in history to rescue us from the worst outcomes of that frailty, first by giving us rules, then by giving us teachers, and finally by coming to live directly among us—and to set a profound act of love between God’s judgment and our failures.

- No differences we make between ourselves—no difference of wealth, or power, or race, or language, or tribe, or creed, or ideology, or anything else, can change the first fundamental fact: We are all equal in depending on God to save us from the worst of ourselves, and we are all equal in our propensity to get off the rails when we forget about that dependence.

Those are all simple ideas. But they are incredibly hard to live by. Because they’re so hard to live by, we fall into disagreements about what they mean and how we should live them out. And so the Christian church itself is a pretty broken, divided affair.

Because we all search for some connection to spiritual meaning, that desire of ours can get turned into the material for building structures of power—structures that presume to hand out certified, Good-Housekeeping-seal-of-approval Christianity. Some folks get large rewards by claiming to be the masters those structures of power, the ones who claim to speak for the “Christian view.” But of course that claim is built on a false premise—because all of them, like all of us, are all too likely to fall into error, not least the sin of pride.

If you listed out the values that lie at the core of those simple ideas at the heart of Christianity, you come up with things like generosity; forbearance; community; charity; equality.

And if you go back and read or listen to all the words that were said in our nation’s capital yesterday, you will find that those values didn’t really get too much attention. It would fair to say that they weren’t just not mentioned; they were mocked.

We are fools if we believe in those things. We are fools to follow a God who reminds us that our fundamental equality is always more important than an distinctions we draw between people, not just in the next world but in this one. We are fools to believe that we best serve our own interests by serving others. We are fools to believe that our own well-being depends on much, much more than ourselves alone, that we are not the unchallenged masters of our own destiny but that our destiny is caught up with the well-being of others.

We are fools to believe that. And that is what we believe. That is what our faith teaches.

More and more, friends, we are going to be regarded as fools. The wisdom of the cross, the idea that God’s grace is not just a decoration of our lives but the necessary condition of our lives together, that wisdom is seen as ridiculous, or disgusting, or sad, by through the lens of our culture—not just one man, but our society.

So if we are going to stick with what we believe, with what we know to be true, then we are going to have to stick together. It is going to be all the more important that we support each other, show up for each other, to live out the paradox of the foolishness that reveals the wisdom God has shared with us.

We are going to have to be the United Fools’ Church—the Saint John’s UFC. We’ll learn from those other UFCs that you get farther and gain more supporters when you join forces—when you work together.

For Christians, to be fools is no criticism. What is criticism is when people find us to be afraid—afraid of change, afraid of generosity, afraid of any other human made in the image and likeness of God.

It’s easy to fall into that trap of fear. That’s why Paul’s instruction to be united isn’t just good advice, it’s the key to our future. To stave off the fear, to be fools bravely, we will need to be united. We need each other to do our collective work of sharing the wisdom of the cross with a foolish and fearful world.

I started in Britain, and so I will end in Britain. Practically in the middle of England, in the region of Leicestershire, there is a church that has the remarkable distinction of having been built in 1653. That might not strike you as unusual unless you know that England was in the midst of a civil war in 1653; the king had been executed by a populist uprising led by a humorless, self-involved leader named Oliver Cromwell.

Cromwell was a man with a long list of things he hated, but near the top of that list was the Church of England. Even after all of the wars and all of the bloodshed between Catholic and Protestant factions a century before, the days Cromwell were some of the darkest and most trying times for the church that we come from.

Cromwell was a man with a long list of things he hated, but near the top of that list was the Church of England. Even after all of the wars and all of the bloodshed between Catholic and Protestant factions a century before, the days Cromwell were some of the darkest and most trying times for the church that we come from.

A wealthy young man named Robert Shirley decided that the best thing he could do to help the people of his village through that dark time was to build a church. And in the village of Staunton Harold he did just that; he paid for a beautiful little village church, a Church of England church, which earned him the ire of Mr. Cromwell, who thought he should have instead have spent the money buying a ship for the navy. So young Robert Shirley was arrested and thrown in prison, the building of the church was made to stop, and not long afterward he died there, before he had reached the age of thirty.

Robert Shirley never saw the church he had begun brought to completion. He died in 1656, three years after starting the church that got him arrested. But just three years later, Cromwell had died, the civil war had ended, the monarchy was restored, and the church was no longer suppressed. Robert Shirley’s son saw to it that the church his father had begun was finished, and it still stands today.

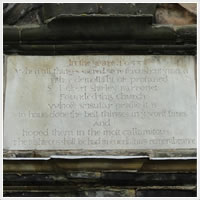

You might think it was a pretty foolish thing for that young man to stand up for the church in the way he did and in the time he did. It cost him a great deal of money, it got him thrown into jail, it probably cost him his life. But if you visit that church today, you will find this inscription over the door:

In the year 1653 when all things Sacred were throughout ye nation, Either demolisht or profaned, Sir Robert Shirley, Baronet, Founded this church; Whose singular praise it is, to have done the best things in ye worst times, and hoped them in the most callamitous. The righteous shall be had in everlasting remembrance.

That is the sort of fool we should all aspire to be. If we work together, we can be. Amen.