Are You on The Bus?

Text: Psalm 42:5:

Why are you cast down, O my soul,

and why are you in turmoil within me?

Hope in God;

for I shall again praise him, my salvation

and my God.

"There are going to be times,” says Kesey, “when we can’t wait for somebody. Now, you’re either on the bus or off the bus. If you’re on the bus, and you get left behind, then you'll find it again. If you’re off the bus in the first place—then it won’t make a damn.” And nobody had to have it spelled out for them. Everything was becoming allegorical, understood by the group mind, and especially this: “You’re either on the bus ... or off the bus."

When I was an undergrad at Emory I worked in the theater building sets. Around my Junior year, they hired this hip new artistic director from Yale with long hair and wild ideas. Half the drama kids loved him. Half thought he was a poser. I thought he was a poser. He knew he was being provocative and that there was some resistance to his provocations, so after outlining some weird production ideas for an upcoming play—ideas that seemed right out of an acid trip—he’d end by saying, “You’re either on the bus or off the bus. If you’re on the bus, I love you and let’s get to work. If you’re off the bus, see ya later.”

I was a little young when Tom Wolfe’s counterculture classic, The Electric Acid Kool Aid Test, was published in 1968, so I didn’t get his bus reference right away, but since then—even though I still think that guy was poser—I’ve found myself returning to that question many times in many circumstances. Am I on the bus?

• • •

Central to today’s lectionary readings is Paul’s Letter to the Romans. Paul used his letters to the various nascent Christian communities to try to tamp down disagreements and mold the churches into a common theology. Christianity was all so very new. Was it an evolution of Judaism? Was it a sect of Judaism? Was it a different religion entirely? Paul couldn’t be in all places at once, so he sent letters to give his advice, sometimes strongly worded advice, to these communities who were forging something new with little precedent.

The church in Rome was no different, but the issue that they were struggling with cuts directly to the question of identity. The Romans were arguing about how to become a Christian. The Christians of Jewish heritage believed that the path was only through Judaism, and that Gentiles had to first be converted to Judaism before they could become a Christian. The Gentile Christians argued that they deserved equal privileges with the Jews, and even looked down on the Jewish Christians because the Jews had, they argued, rejected and ultimately killed Jesus.

What made the church in Rome unique, however, was that they didn’t have a first-hand experience with Jesus or his apostles to draw upon. The church was not so much founded as just simply became as the good news of Jesus’ ministry trickled organically in to Rome. This made Rome a perfect place for Paul to not only address the issue of “Christian admission,” but to more broadly lay down his theological treatise as a guide for those distant Christians. In this way, the Letter to the Romans is considered by many scholars to be Paul’s masterwork of doctrine. Indeed, the first chapter of Romans contains the famous “Reformation Text” that Martin Luther credits with opening his eyes to a new understanding of righteousness and faith.

If you’ve spent any time with the epistles, you know that Paul has a particular and peculiar style of writing, with quick dips into side comments and an almost unnatural love of pronouns. To me, reading the “Epistle Appointed for Today” is the hardest part of being a Lay Eucharistic Minister, and if you’ve been keeping score, you’ll know that, when serving as LEM, I’ve never read the Epistle completely through without a hiccup.

So it should be no surprise when I admit to you that I have had a lot of trouble parsing today’s text. It was not just the phrasing but the meaning that gave me trouble. After reading it about thirty times, I came to realize that my primary obstacle was one word: Justified. In verse 1 Paul says, “Since we are justified by faith…” and later in verse 9 he writes “now that we have been justified by his blood.” Both of these phrases seem to suggest that our belief in Christ somehow inoculates us against prosecution. I came in with the Old West interpretation. “Yup, he’s dead awright. But he’s a cattle rustler, so you was justified in the killin’.”

Here in Romans, “justified” does not carry that meaning at all. It does not inoculate us against who we are, but against who we were. It’s transformational; the connotation is that the object—we, the ungodly—are being trued up, like aligning text in a Word document. By faith in Christ, we are literally coming into alignment with God.

• • •

Now back to the argument between the Romans. What, then, is the admission criteria for being a Christian? The logic that leads the Romans, and even us, to assume that there exists an admission criteria is actually easy to follow. If you have a group of people, then this group must be defined by some common characteristic that makes them a group. If you possess that characteristic, you are in the group; if you don’t, you aren’t. So achieving the characteristic is the admission criteria. If you view Christianity as a natural evolution of Judaism, and that Judaism is foundational to Christianity, then it follows that you need to be Jewish first to then become a Christian. If you aren’t Jewish and don’t really want to be, then you may disagree. Paul’s answer is simple and beautiful: “Since we are justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ.” The only admission criteria we need is faith that Christ died for us, and therefore we are justified—that is, realigned—in our relationship with God.

Need an example? When the Samaritan woman meets Jesus at Jacob’s well, she likely arrived thinking it would be a day like any other. She lived in a society defined by her country (Samaria) and her religion (a branch of Judaism despised by the “proper” Jews). Plus, she seems to have some suspicious living situation. Yet Jesus engages with her, breaking social conventions and quickly disarming her with metaphorical responses to her literal questions. By the end of the encounter, this woman has been transformed, realigned. Where she came to the well thinking that she knew her place, and looked no further than that, she left with faith (“He cannot be the Messiah, can he?”).

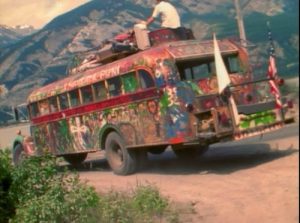

Was the Samaritan woman “on the bus”? In The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test, the bus is both real and figurative. Ken Kesey and his band of hippies—the Merry Pranksters—were driving a psychedelically painted 1939 International Harvester school bus from California to New York for the 1964 World’s Fair. Every time they stopped for gas or food, some of the Pranksters would wonder off, and Kesey eventually got annoyed. When he yelled at them about either being on the bus or off the bus, he was saying, “You’ve either bought into this movement, and you’re on board, or you’re just messing around, and you’re not on board.” Being on the bus came with an admission criterion.

We face our own buses every day. Sometimes these buses are easy to get on, like in sports, when they are generally called “band wagons.” Sometimes they are harder, like when we must decide between competing visions of leadership. But sometimes we just stand outside the bus wondering if we can take that step, or wondering if we’ll even be allowed to.

Paul, as we’ve discussed, answers the second question. Are we allowed to get on the bus? Yes! How? Through faith. Not through birthright. Not through conversion. Christ has justified us. All we have to do is have faith in that justification.

But the first question—can we take that step—is a stickier issue. Interestingly, Paul helps us out here too. Let’s see. Here it is: “But we also boast in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us.” Who among us has not suffered? If we’ve suffered, then by a series of deductive steps, we have hope, and hope does not disappoint. QED!

But it isn’t that simple, is it? If it were, then no one suffering from cancer would fail to recover. No one would die from injuries sustained in a car accident. No one would watch as a loved one, in despair, turned to drugs or alcohol or worse. No one would have lost a homeland to civil war.

If hope does not disappoint, then why are we so often disappointed, in spite of how much we hope?

In today’s reading from Exodus, the Israelites were clearly suffering as they wandered in the wilderness without water. I’m sure when they left Egypt, there was a ton of hope for a future free from the yoke of slavery, but what good is that freedom if you die of thirst in the dessert? If we put ourselves in the shoes of the Israelites, is it so unreasonable that we would be pressuring our leader, Moses, to find water, a basic need for survival? Notice what happens: God gets exasperated, God gets annoyed, but eventually God produces the water. What exactly are we supposed to learn from this? Maybe the lesson is that God will provide. That is a basic tenet of our faith, isn’t it? God gives us no weight greater than we can bear. Christ picks us up when we fall. The Holy Spirit guides us when we are in peril.

I’m afraid that I think those tropes are a bit naïve, and I tell you that, as I speak this out loud, I feel like I’ve committed a heresy against God and every Sunday school teacher I ever had. But let’s face the facts. We live in a world where nearly nothing honors our deep hope or even our deep faith. Bad things happen, and they seem to happen regardless of how much we implore heaven to forbid it.

With his blood, Christ has bought our ticket to get on the bus, and with no more than our faith in this redemption, we are welcomed aboard. Our hesitation, however, comes when we think that getting on the bus is some sort of a contract, where we live in faith and, in return, God provides for us through hope. Human nature insists that there is a quid pro quo—we believe, and in return water comes from the struck rock.

I want to get on the bus. I really do. But I struggle to have faith in a real and present God when I see so much evidence that supports doubt rather than belief. Proving that God is real and present, and doing so in any truly satisfactory way, is far above my pay grade as an occasional preacher. I’m not at all equipped to answer that question, and if I try you’d see right through me as a poser.

My solace comes from the fact that no one here on earth has the answer to doubt. And the irony of it all is this: Not having the answer, right here and right now, is a very good and proper thing. Because doubt produces struggle, and struggle produces contemplation, and contemplation nibbles on the edges of understanding, and those edges show us where we need to apply faith, and it is this faith—born of doubt and struggle and contemplation and snippets of understanding—it is this faith that truly does not disappoint.

I’m standing at the door of psychedelically painted 1939 International Harvester school bus. I have my doubts. But I have my ticket.

Come on, Tim. Are you on the bus, or are you off the bus?

Amen.