Fundamental Forgiveness

The lessons for this day are found at this link.

Text: Matthew 18:33: “Should you not have had mercy on your fellow-slave, as I had mercy on you?”

The clear and unavoidable theme this morning is forgiveness. That has been true for as long as we have followed the disciplines of the lectionary; not quite from before time began, but at least for the last forty years or so, this gospel reading was going to fall on our ears today.

It is a teaching about forgiveness, a teaching that takes the form of the answer to Peter’s question about how much forgiveness he is expected to show toward a member of the church. He doesn’t really seem to consider that he needs to figure out how to forgive people outside the church. Peter’s question is about the quantity of forgiveness expected of a disciple; but the answer he gets is about the quality of forgiveness that is expected of us.

But I am getting ahead of myself.

One of the deepest satisfactions I have found in getting older are the moments in which I discover I am being taught something by someone I first knew when they were students. That happened to me this week, when a young woman I first knew during her undergraduate days brought to my attention an article in this past Thursday’s New York Times on the subject of forgiveness. As it turns out Mattie Olsen became a teacher, back in her home state of Nebraska, and I have every reason to think she is an excellent one.

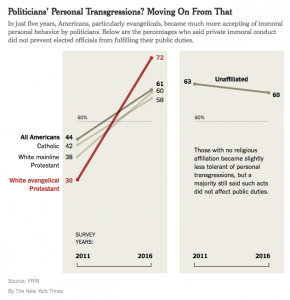

The article she shared is by Thomas Edsall, who has made something of an industry out of studying the divides and divisions of our political life. And what it specifically looks at is our attitudes around this question: Should we forgive our politicians and public figures for their personal moral failings?

Now, this is not such a straightforward question. We want our leaders to be examples of some kind; to be role models. We also live in a democracy, and so we are quite accustomed to the idea that we should hold our leaders to account.

The question is, whose account? What standards?

Source: Thomas B. Edsall, "Trump Says Jump. His Supporters Ask, How High?" New York Times, September 14, 2017; https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/14/opinion/trump-republicans.html

What Edsall’s article points out is that attitudes on this question have shifted pretty dramatically in our country over the past six years or so. Those who identify themselves as some flavor of Christian have become, apparently, a lot more forgiving of our public officials. In fact it seems that the more conservative you are on the Christian spectrum, the more willing you have become to extend forgiveness toward our elected leaders in the last, oh, year or two.

But there’s another finding that’s just as interesting. It’s that people who are unaffiliated with any religious tradition-—that growing sector of the population—were less inclined to extend that forgiveness to our public leaders.

I don’t think it’s too easy to draw clear conclusions from this. It seems to me the folks who aren’t part of any religious community are just about equally likely to be liberal or conservative. And the same turns out to be true for those who call themselves Christians, at least if you put them all together.

What I do wonder about, though, is how much of this is about a convenient sort of forgiveness. The sort of forgiveness that reflects our preferences, or at least our willingness to overlook the faults of those who, in our increasingly polarized world, we somehow imagine are on “our side,” and to demand a full accounting for the failures of those who are not.

The answer Peter gets to his question this morning comes in the form of a parable. It focuses on the ethical choices of someone who has already been forgiven, and it asks a basic question of moral conduct: Why have you not extended to someone else the mercy that has been shown to you?

When Jesus offers this answer to Peter’s question, he is shifting the ground away from a kind of accountant’s answer to an artist’s answer. It becomes a lot less about how much, and a lot more about just how—how we should live, how disciples should think of themselves as moral agents in the world.

When that slave forgets to extend to someone else the forgiveness he once received, he shows that the fact he was forgiven made no real difference in his life. It didn’t do any more to open his eyes to his own capacity for getting it wrong, and it didn’t change his perspective when it comes to others who do the same. He didn’t understand that he was forgiven in some fundamental way—a way that is meant not just to balance his checking account, but to free him from debt, period. He missed the opportunity he was given.

Now here is the part that is just as uncomfortable for our twenty-first-century American ears as it was for those first-century friends of Jesus. We, brothers and sisters, we are meant to understand from the answer that Jesus gives that we are slaves.

We have been forgiven. Not just excused. Not just accepted. We have been forgiven in a fundamental way.

And here is the even harder thing for us to grasp. We needed forgiveness. Something about us, something about this complicated, conflicted person each one of us is, this struggle between desire and will, this mixture of holy and hot mess, puts us—without any consent from us—in a place that we need the mercy of forgiveness. Whether we know it or not; whether we like it or not; whether we agree with it or not.

And, let’s face it; we generally don’t agree with it. We think of ourselves as, you know, pretty good people. After all, we go to church. We make mistakes, but they’re not huge mistakes. Okay, well, maybe some of them have been bigger than others, but everyone is a good person in the core of their being, right?

We want, we really want, to think that. We are unwilling to accept the alternative. But if you think that, not a lot of what the church stands for, or what we do here, will really be all that important to you.

If in the end we don’t really think we stand in need of forgiveness, then all of this is not going to amount to much more than a habit, or a comforting routine. It won’t bring us to any great realization about ourselves or change us in any way. And if that’s the case, then at some point we’ll feel as though we can take it or leave it.

But if you do grasp that you need that forgiveness—if you do start from the idea that somehow what is being offered to you by God isn’t just nice, but urgently necessary—then you will hang on to this for dear life. Because dear life is exactly what it gives you.

Jesus doesn’t only tell parables about this. He lives it out in the real world. Remember that at a different moment in the story Jesus comes upon a scene where a woman is about to be stoned to death by a mob because she has done something they regard as unforgivable. For them, the only path to justice isn’t forgiveness, it’s shame. It’s condemnation. It’s death.

You know how that story goes. Jesus draws a line in the sand—both figuratively and literally. He offers the idea that anyone who hasn’t ever done something that might be categorized as unforgivable should feel welcome to throw that stone. And in that moment, they all realize, every one of them, that they all are slaves, fundamentally forgiven slaves, just like she is.

I’ve probably quoted Howard Thurman from this pulpit before, but he always quotable. Howard Thurman was the dean of Marsh Chapel downtown in the 1950s, a place where among other things he was Martin Luther King’s preaching professor.

When Dean Thurman preached about the story of Jesus and that woman and that mob, he says that in the moment Jesus posed that challenge to the mob “each man saw himself in his literal substance. In that moment each was not a judge of another’s deeds, but of his own.”

But that isn’t the end of the story. Jesus doesn’t just excuse that woman’s mistake, and he doesn’t just excuse ours. He doesn’t just pretend it didn’t happen.

Here’s how Dean Thurman’s sermon ends:

He met the woman where she was, and treated her as if she were already where she now willed to be. In dealing with her he “believed” her into the fulfillment of her possibilities.... He placed a crown over her head which for the rest of her life she would keep trying to grow tall enough to wear.

If you think you are already where you will yourself to be, then the what the Christian story has to offer you won’t mean much to you.

If you have already made your own crown for yourself, and are contented with that, then you won’t be that interested in growing into your full possibilities to rise up and wear the crown God is holding over you.

If you don’t think you stand in much need of forgiveness, then it will be very easy for you to have a heart made up of those stones gathered at the feet of that mob. It will seem like the righteous thing to pursue the good cause of justice through the means of shame, and condemnation, and even death—a death of human kindness, a death of mercy.

But if, like the men in that mob, we can somehow find the grace to hear those words of the gentle judge and suddenly see ourselves in our literal substance; if we can see ourselves in that slave’s moment of desperate emptiness and know in the very core of our soul that forgiveness is not an option for us, but a requirement—then we will know just how fundamentally forgiven we are. We will know why, and how much, this all matters. Our forgiveness will be our practice, and not just about our preference. And that, by the grace of God, will work in us the change that will give us the hearts of disciples. Amen.