Weighty Words

Sometimes the lectionary offers a group of lessons for Sunday morning that seem to speak directly to the issues of our day. Sometimes they don’t, and when that happens, as any of my colleagues in the Sermon Group will tell you, you can find yourself sitting down with your Bible and your books and your computer, staring at the screen and wondering what it is you’re going to have to offer that Sunday morning.

And then sometimes the lectionary presents you with a theme that is certainly important, and obviously right there in the readings, but sort of uncomfortable, or maybe awkward, to deal with. Today is one of those days.

Let’s just remember at the outset that this is not just any day. This is the last Sunday of January, and in most Episcopal churches, at least the ones around us, that means it is the day that the Annual Meeting of the Parish will take place. The Annual Meeting is not optional; it’s not a tradition that we have to make sure we have a potluck lunch in January. It is something core to our identity as a church.

The Annual Meeting is the moment in the cycle of the year when we contend with a topic that is never easy, or simple, or straightforward for those of us who live in the Western world in the early twenty-first century, and especially those of us who live in the United States. And that topic is authority.

We know, in some abstract way, that authority is necessary to the way society works. Authority is the way we create and maintain some kind of order in our political and economic lives. Without order there is chaos, but without authority there can be no order.

But authority is a complicated subject for us. Authority is someone else having the power tell you what to do, or what not to do; what is allowed, and what is not. We don’t take well to that. We want to decide for ourselves what we think, what we do, what causes we join, what values we hold.

This morning we elect our Vestry, and collectively we give them the authority to run the church on behalf of all of us. We trust them with the stuff—the building, the money, the utility bills, the tenants. We expect them to be responsible for these things; they can’t exercise that responsibility without authority. Authority and responsibility go together.

One of the fundamental errors organizations often make—whether they are churches, or schools, or governments, or companies—is to fail to distribute authority and responsibility in linked ways. We love the idea of delegating responsibility, but we are a lot more hesitant to delegate authority. And when that happens, trouble always follows.

There is a different kind of authority spoken of in the readings this morning, though, something that is held out there as having pretty high importance for our spiritual selves. It is the authority of the leader of the community—where it comes from, and what it is for.

Moses has been the great leader who liberated Israel from slavery in Egypt and led the people out of that place and into both a promised land and a covenant relationship with God. At the beginning of the story he was about the least likely person to be tapped for the role; by the end of the story, no one can imagine Israel without him.

But they will have to imagine it. Moses is mortal. He will not always be there to lead them. Somehow, for the people to still understand themselves as a community, to stay connected to each other for the purpose of living out the covenant they’ve made, someone else will need to exercise that authority—someone from right among them.

So Moses is teaching here about where that authority comes from. It comes from the ability, the willingness, the discipline of that person to listen carefully to God in prayer, and to communicate faithfully to the community God’s hopes, God’s love, and God’s expectations.

The sort of person Moses is describing is the sort of person Jesus turns out to be. This morning Jesus is exactly where he’s supposed to be on the sabbath day; he’s in church. And he’s teaching. He’s a little outside of his own hometown, but he’s in his own part of the world. He’s one of them, speaking among his own people. And yet his own people hear something new in what he has to say.

What’s new is not what he’s preaching. What’s new is the clarity, the power, the persuasiveness of what he has to say. Jesus is calling people back to the core ideas of the covenant relationship that is their inheritance from Moses. He is reminding them that what’s at the very center of that covenant is not a set of laws outside them, but a heart inside them—a heart that needs to be shaped by the constraints of those laws.

That’s not new. What is new is the authority he seems to have when he says these things. For the first time, it seems, they are hearing anew a very old truth.

Now, here is where this set of ideas turns awkward. Because in this place, and among all of us, we need to find our way clear to accepting that authority, and following it.

There is a way in which all of these stories have an unsettlingly familiar ring to them. Because after all, more than is almost ever the case, we have a rector who is from among us. That’s me. And you might think that where I’m headed with this is in the direction of claiming that authority for myself.

But in the church—the capital-c church—that authority still belongs to Jesus. Moses died and needed to be followed by someone else. Jesus died and was resurrected. We say by faith that the church is the living body of Christ. So we haven’t had to find a substitute, or a successor. The authority of Jesus still lives right in our midst.

What is different about this church is the way we share that authority. In the old days, we sort of saw the ordained person as the single person to whom that authority was delegated. But that is not true here. Over the past years, we have shared in new ways among ourselves both the responsibility and the authority for the work we do together.

I know that it has not always been easy, and I certainly know that it has not always been fun. But it seems to me that in doing this we have rekindled among us something that was true in the very first churches; a sense that this ministry, this calling, this high purpose of ours here in this moment and in this place is something we all have a stake in, something we all have a part in—not just the person standing here talking right now.

We even share this role in the place, this role of praying through, reflecting on, and speaking in the midst of the community about what God is calling us to do.

Even so—I do still have that same responsibility that Moses talked about. It falls to me, or to the person in this role, even when it’s a person like me who comes from right out of the pews of the place, to speak as clearly, as persuasively, and as effectively as possible what I believe to be God’s hope for us—and God’s expectations of us.

I am always aware that the only things that separate me from the sin of presumption are careful study on my part, and a willingness to listen on your part. Without both of those things, none of this works, and God is neither praised well nor followed well.

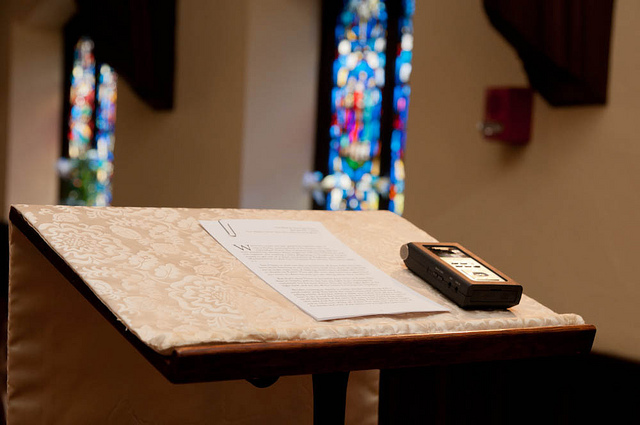

So these are weighty words, the words that get spoken from up here. No matter who says them, they are meant to remind us of the need for authority in our lives together as a community of God’s people. And they are meant to be an exercise of that authority, for eleven minutes every Sunday morning, for our collective good. Amen.