Fall and Rise

Text: Romans 5:18: “Therefore just as one man’s trespass led to condemnation for all, so one man’s act of righteousness leads to justification for all.”

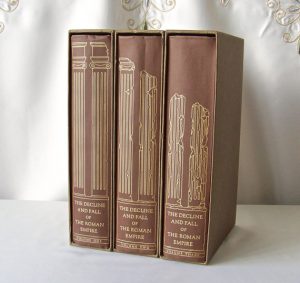

Probably about the first book I ever bought for a purpose other than reading an assignment in school was a used copy of a three-volume edition of Edward Gibbons’ great history of the ancient world, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. I would like you to think that I bought it because of my deep interest in ancient history, but to tell you the truth what first drew me to it as I walked through the aisles of the used booksstore was the binding.

It’s a long work, seventy-one chapters long, originally issued in six volumes. The edition I saw there on the shelf that day was bound in three thick volumes, and on the spine of each was a design of Roman columns, two columns on each volume. But as you looked at those six columns, what you noticed was that the first one, on volume 1, was perfect; and that as your eye moved from left to right across the three spines of those books, each next column was more decayed and broken down, so that the last one was little more than a ruin.

The design of those bindings perfectly and wordlessly conveyed the ideas within those three heavy books. Rome, the great achievement of the ancient world, had begun as a republic that expressed in political structures the civic virtue of its citizens. It had become an empire focused on conquest and domination; the citizens had become willing to trade their values for monetary gain; and the great empire finally collapsed, because its citizens no longer possessed the self-discipline and regard for virtue that had built the republic in the first place.

The basic idea of Gibbons’ history has become, for us, a kind of basic idea, a cultural trope. We sort of relate it to as the inevitable way that history follows the laws of physics, and specifically that bit about what goes up must come down.

Nations rise and nations fall. Egypt, Athens, Rome, Byzantium, the Incas, the Aztecs, the Spanish, the British, the French—the story of human civilization is a story about ups and downs, about ascendance and decline. That seems as much a law of nature as the fact of human mortality. Living as we do in this remarkable nation at this turbulent moment in history, sometimes we wonder where we might be on that arc of rise and fall. Of course, our ancestors wondered about that, too. There’s nothing new about that particular brand of worry.

Rise and fall—that is the story of human history. It’s a reflection, at the largest scale, of our own frailty as humans. We love to believe otherwise—and from time to time we are absolutely certain, as Dr. Pangloss said, that all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds; that every day, in every way, things are getting better and better. But then we are confronted with the hard edges of reality, and we come to a different view.

I’m not saying all this to start your Lent out on a downer. On the contrary, there is a method to this misery. The point of all this is to make a contrast between our lives in history and our lives in God. Because it turns out that our lives in God, the lives of our eternal souls, head in a different direction, toward a different destination.

Just this past week, on Ash Wednesday, we entered again upon the season of Lent. Our lives in history are played out in the cycles of days and weeks and years, and the church gives us the gift of a way to moving through those cycles with an order, a structure, that we would otherwise have to create for ourselves.

Because we don’t have to do that, we can instead focus on the ideas that unfold week by week, month by month, in the calendar: anticipation, preparation, incarnation, manifestation, penitence, self-examination, sacrificial passion, resurrection, discipleship.

Those aren’t the names of she seasons, but it is, in a simple way, the sequence of ideas set before us. There is a kind of internal logic to them; and if we take it even a little bit seriously, each time around the cycle we can explore those ideas a little more deeply.

• • •

Where we are headed in this season of Lent is to the cross, and the grave, and—at the end—to the empty tomb, and to the defeat of death itself. But none of that makes a lot of sense, none of that is likely to mean much to any of us, unless we start at the beginning, and understand how our story starts.

The Book of Genesis is not an astrophysics textbook. Let me say this plainly: The Book of Genesis is not a historical record of the creation of the universe, the planet, and the creatures on it. It’s not that.

But we are often so anxious to say what it isn’t that we are at some risk of forgetting what it is. It is a map of the universal human spiritual journey. It is an account of the situation from which we all begin, and it is only by fully taking that on board that we can have anything like an appreciation of just what is so insanely joyful about Easter.

Let’s say that we accept the account of creation given to us by scientific reflection. Most of us do, I expect. It gives us a set of ideas about how we came to be who we are; we are here, as we are, rather than some other species or some other kind of human, because certain kinds of traits turned out to be more advantageous in helping you survive than others.

Some of those traits we’ve wisely come to regard as virtues to be treasured, encouraged, and celebrated. Things like altruism, and socially constructive behavior, and stable, long-term commitments in pair bonding, and actions that put the interests of others clearly and squarely before one’s own self-interest.

And some of them we regard as things to be admired just because they’re examples of the highest expressions of humanity—feats of strength, or athletic skill, or intellectual prowess, or creative ability.

But what comes with all of that is some other things that helped us survive, things that aren’t so good. We instantly and automatically make assumptions about other humans. We place great stock in observable differences—skin color, eye color, the structure of someone’s face, the way they speak or walk. We are hard-wired to create rank, and to put some people, and often ourselves, above others.

What comes with all our great skill and our tremendous advantages is an equally large share of stuff that makes us dangerous to ourselves and others. The things about us that are the best, the things about us that are the image and likeness of God in our hearts and our minds—we can do serious damage to those virtues, in ourselves and in other people.

That tendency, that dangerous inclination and all the stuff that comes from it, that’s what we mean when we say “original sin.” We don’t like the sound of that phrase; it makes us feel bad, or judged before the evidence. So we try to explain it away or throw it out as old thinking or oppressive.

But paradoxically, it’s actually liberating. Because if we try to throw it out, we throw away as well an understanding not just of the trouble we’re in but the way we get out of it.

• • •

For Paul, writing to the church in Rome, old Adam is a stand-in for all of that. We are caught up in Adam’s sin for the simple reason that we are human—and Adam is that first human who found himself snared in this trap between tremendous skill for good and tremendous tendency for trouble.

Adam’s prison is our prison. We didn’t make it for ourselves; you might almost say that it made us. This prison of the quest to survive and endure over hundreds of thousands of years made us both skilled and suspicious, both capable and culpable.

So that’s where we are stuck. That is the death we cannot escape. Racism, intolerance, indifference to suffering—all of that is the death that traps us. It comes with the coding. In the end so does fact of our mortality, which is what pushes us so hard to struggle for survival in the first place. That is the trap we’re in.

To say it in different words, unlike the rest of history, we don’t rise and fall. We fall and rise. We start with the fall. Our lives in God start with the fall.

Lent is a reenactment, in the tiny space of forty days, of our whole story of salvation, a story that exactly reverses the way the rise-and-fall cycle of the rest of history. We don’t start in some high and lofty place and come crashing down like a collapsing empire.

No, our spiritual story starts with the fall, with the poor reflexes and self-destructive instincts that are quite literally baked into our DNA. And we end by being given a path out of that trap. The bars of the prison that made us, and which we, in turn, have only made stronger, are shattered completely.

That is what is done for us by the person, the teaching, the actions, the sacrifice, and the resurrection of Christ.

And here’s how he does it: Every one of our lesser tendencies—our hesitant generosity, our reflexive rank-ordering, our insistence on inventing some kind of meaning out of the differences we can observe in others—absolutely every one of them Jesus completely upends by the example of his life. He shows us what a life would look like, how it would be lived, what it would sound like, if it were not beholden to any of those weaknesses.

The greatest gift of all, the gift of Easter, is the gift of some way of overcoming those weaknesses ourselves, and for finding ourselves a path that leads us back up to the high place we are meant to be.

All of that is packed into these forty days of Lent. My prayer for us, my request of us, is that we find somehow in the routine of every day just a moment, just one moment, to think about the ways we feel trapped in that prison.

The ways we feel somehow caught up in a place we know is less than where God intends for us to be, mired down and stuck right here and unable to move up higher.

Because then this season will become more than a story; it will become what it is mean to be, a way of taking stock of the extent of our trouble, and a way of finding the way God is giving us to walk out of it. Amen.