The Shadows of Light

[No recording is available for this sermon.]

Text: Acts 1:14: “All these were constantly devoting themselves to

prayer, together with certain women, including Mary the mother of Jesus, as well as his brothers.”

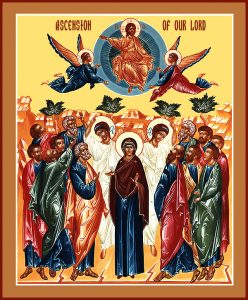

This is an odd sort of day in the church calendar. It’s the Sunday after Ascension Day, which was just this past Thursday. Ascension Day is always on a Thursday, because it’s always forty days after Easter Sunday, and no matter how you count that out you will always land on a Thursday.

These days Ascension Day passes by without so much as a whisper, even though to the ancient church it was a very big deal indeed. It marked the end of the earthly appearances of Jesus after the Resurrection; but more than that it came as a sort of reinsurance policy.

Jesus had defeated death and returned to life, and that meant we were given the assurance of victory over death, too. But then Jesus disappeared from the sight of the apostles and, as the angels taught them, rose into heaven. And then they remembered what he had said about preparing a place for them in the mansions of heaven, and they got it—it wasn’t just that we were given the assurance of victory over death, but an entrance into heaven as well.

Ascension Day also stood as a kind of threshold through we enter into a completely new order of time. It is the gateway through which we pass from the brief life of Jesus to the era of the church. Next week will be Pentecost, when we remember the coming of the Holy Spirit to equip us not just to proclaim the resurrection of Christ but to be the living body of Christ.

But there is one other threshold that Ascension Day represents. Because Jesus ascends into heaven with a round-trip ticket. He will return in a moment the ancient writers described as the end of times. And when that happens we will have to give an account of ourselves.

So there is a lot of drama and some really good special effects in the story we remember on the Sunday after Ascension Day. But for some reason this year as I reflected on these readings some weeks ago, my attention was drawn to just one verse from the reading from Acts, a verse I’m not sure I ever noticed before in a lifetime of reading this story.

So there is a lot of drama and some really good special effects in the story we remember on the Sunday after Ascension Day. But for some reason this year as I reflected on these readings some weeks ago, my attention was drawn to just one verse from the reading from Acts, a verse I’m not sure I ever noticed before in a lifetime of reading this story.

It’s the little summary of what happens after all the amazement and the clouds and the disappearing act and the angels. After it all happens, the confused and astounded apostles go back down the mountain—Mount Olivet—and they have to begin being the church. And this is what the text says they do: “All [the apostles] were constantly devoting themselves to prayer, together with certain women, including Mary the mother of Jesus, as well as his brothers.”

Okay, wait a minute. “As well as his brothers”? What brothers? Who are these brothers?

We never hear a lot about the family of Jesus, at least not outside of the Christmas season. We sure never hear in any substantial way about his siblings. Maybe that never struck me odd when I was growing up, because I was an only child. It didn’t seem to me unusual that Jesus didn’t have brothers or sisters because, well, I didn’t either.

But right here in the first chapter of the Acts of the Apostles—my gosh, there they are. And the more I thought about that the more I wondered—what do you think it would have been like to have Jesus as your brother?

I think it wouldn’t have been very easy, don’t you?

We know that Jesus was the first-born child, so he was the eldest of the family. And it’s not like he’s ever doing anything wrong to make it easier for you to plead your case. He’s always good. He’s always considerate. He always does his homework. He always writes his thank-you notes. If Jesus is your brother, well, he’s probably sort of insufferable.

But what the story tells us is that those siblings weren’t jealous, they weren’t resentful. They didn’t complain about not getting their fair share of the attention or the glory. They were part of the followers—they were part of the movement. They weren’t even the best-known or longest-remembered part of the moment. We don’t really know their names. We don’t name churches after them. We just know they were faithful, and right there alongside the disciples, and otherwise obscure.

There is a dignity, even a nobility, in that. We might say that we’d prefer not to be the center of attention, that we prefer not really having to have a high-profile public life; but there is a kind of attention that all of us need, and can’t really do without; the attention of being seen, of being loved, of being, in that wonderful old word, beheld. We want at least to be the center of that attention.

And if you’re the one whose sibling is the great shining light in the world, well, what you learn is that great shining lights create dark shadows as well. And those shadows can be a difficult, even a forlorn, place to be.

Maybe it is not an accident that we are reminded today of the rest of Jesus’s family, the ones we could easily forget simply because of the significance of his story to our lives and our faith.

Because by an odd coincidence those words come around to us not just on this Sunday in Ascensiontide, but on Memorial Day—a day we set aside for remembrance, exactly to stave off the easy temptation of forgetting and overlooking the humble, the quiet, and the obscure.

I have a friend whose mother and father are buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Her mother died not too many years ago, and she lives pretty far away from there. I happen to be in Washington from time to time, and certainly more frequently than it’s possible for my friend to be there, so over the past few years I’ve tried to make a point of visiting there when I’m in town, I suppose out of some idea that my friend might derive some sort of comfort from knowing that place is being visited by someone.

No photograph of that place can do justice to the visceral impact of seeing row upon row upon row of those stones, each one bearing the name of someone, some soldier or sailor or airman or marine, someone’s daughter or son.

That we have set aside this place in the nation’s capital—and that we have devoted such care and such devotion to it—is, of course, a tremendous act of remembrance, of somehow acting to ensure that none of the people who bore those names will be forgotten. Maybe that is why the place of highest honor and most solemn ceremony is given to the one we regard as unknown—unknown, and perhaps because of that never forgotten, not for a single moment of a single day.

And there are countless others who fall into the shadows of obscurity unless we call them to remembrance. They are those who may not have ventured into the chaos and noise of the battlefield, but who yet showed by the example of their lives the deepest and most faithful devotion to the teachings of that man who was the brother of those unnamed followers in the Acts of the Apostles.

I am thinking of such as those homeless men in Manchester, living on the streets for who knows what reason, who rushed to help injured and dying children and their parents after the horrific bombing last Monday.

And I am thinking especially of two young men in Portland, Oregon, who stood up on a trolley car to come to the defense of two Muslim women who were being harassed by an abusive, angry white passenger. And when they came to her aid, they were set upon by that man and stabbed to death by him.

Their names are not yet even known. They may never be known. But their devotion to the cause of the law of love, and their faithfulness to the teachings of the man from Nazareth, of that we can have no doubt.

I will keep them in my prayers this week, and I hope you will, too. I will keep all of those unknown, overlooked, who lived faithfully and gave greatly even though no recognition came to them, even though others gained the fame and the renown. I will think of them as the sisters and brothers of Jesus, coming down the mountainside, ready and eager to get to the work of living their lives by following that light, without regard for reward and without counting the cost. Amen.